After a few days at work (the paid kind, involving sitting in front of a computer or talking in meetings) it's time for the highlight of the week, a day on the railway. Since we are still in the off-season, it's a day on-shed at Weybourne helping out with winter maintenance.

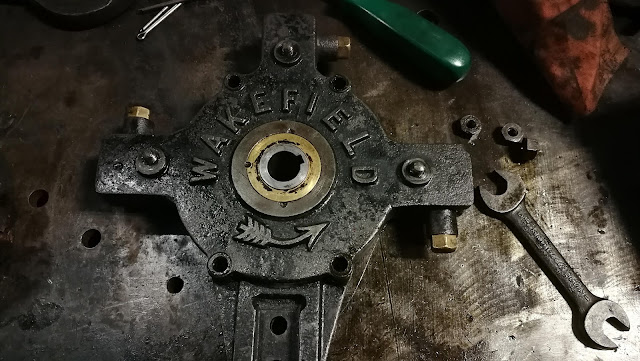

We're working on the BR Standard 4MT, and today it's the lubricators that are receiving some attention. Here's one, laid out in bits:

Some instructions on how it works. These have twelve pumps in each of two lubricators, one for the steam side and one for the axle boxes.

Here we can see the eccentric shaft (K) and the two carriers holding the regulating plugs (G) and the sleeve valves (E). The pump barrels (C) are in the blue box, and you can see their oil ports (F):

Here's one of the pump barrels, dismantled. You can see the non-return valve (H) and it's retaining cap:

Here's the reservoir, upside down:

This is where the lubricator fits on the 4MT.

Underside view of the reservoir with the pump barrels in place:

When complete, each pump has a pressure tight cap:

The view from the inside. the greenish bobbins are the guides for the carrier (W).

Now we are stuck. The camshaft is slightly damaged at the keyway, which has allowed much of the small movement from the driving ratchet to be lost. The camshaft needs to be repaired before we go any further:

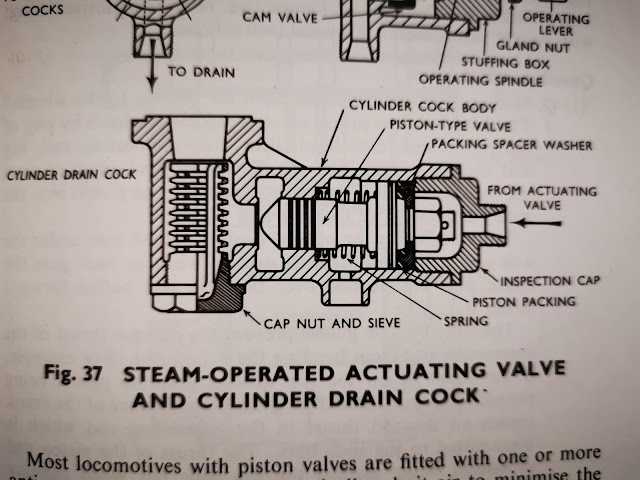

So, it's on to another job. These are the cylinder drain cocks on the left hand cylinder; each cylinder has two, and there is a further drain cock on the steam chest. Their purpose is to drain water from the cylinders (when they are cold, for example) to avoid damage from hydraulic lock.

We know these are weeping steam, so they need to be cleaned out and the seats inspected. They are pilot operated by steam from another valve which in turn is manually operated by the driver:

Here's a diagram:

The inspection caps are very tight. We need a vice, a big spanner and a copper hammer to loosen them:

Here's the piston from one of them, covered in burnt steam oil:

Here's the rest of it:

Having stripped and degreased all four, it's a waiting game again while the piston sealing faces are refinished in the machine shop. Back to the lubricator, and we can strip and clean the ratchet drive:

Elsewhere in the shop, fitters Bob and Paul are removing the smokebox door. It's dropped recently and is difficult to close:

It's off!

The 7F is still have spring work. This simple hydraulic press has been adapted to measure the spring force against deflection:

Outside in the mist, the B12, Y14 and Ring Haw await their turn in the shop. The 4MT is getting all the attention, as there will be a yellow service for Spring Half Term at the end of February.

We're working on the BR Standard 4MT, and today it's the lubricators that are receiving some attention. Here's one, laid out in bits:

Some instructions on how it works. These have twelve pumps in each of two lubricators, one for the steam side and one for the axle boxes.

Here we can see the eccentric shaft (K) and the two carriers holding the regulating plugs (G) and the sleeve valves (E). The pump barrels (C) are in the blue box, and you can see their oil ports (F):

Here's one of the pump barrels, dismantled. You can see the non-return valve (H) and it's retaining cap:

Here's the reservoir, upside down:

This is where the lubricator fits on the 4MT.

Underside view of the reservoir with the pump barrels in place:

When complete, each pump has a pressure tight cap:

Now we are stuck. The camshaft is slightly damaged at the keyway, which has allowed much of the small movement from the driving ratchet to be lost. The camshaft needs to be repaired before we go any further:

So, it's on to another job. These are the cylinder drain cocks on the left hand cylinder; each cylinder has two, and there is a further drain cock on the steam chest. Their purpose is to drain water from the cylinders (when they are cold, for example) to avoid damage from hydraulic lock.

We know these are weeping steam, so they need to be cleaned out and the seats inspected. They are pilot operated by steam from another valve which in turn is manually operated by the driver:

Here's a diagram:

The inspection caps are very tight. We need a vice, a big spanner and a copper hammer to loosen them:

Here's the piston from one of them, covered in burnt steam oil:

Here's the rest of it:

Having stripped and degreased all four, it's a waiting game again while the piston sealing faces are refinished in the machine shop. Back to the lubricator, and we can strip and clean the ratchet drive:

Elsewhere in the shop, fitters Bob and Paul are removing the smokebox door. It's dropped recently and is difficult to close:

It's off!

The 7F is still have spring work. This simple hydraulic press has been adapted to measure the spring force against deflection:

Outside in the mist, the B12, Y14 and Ring Haw await their turn in the shop. The 4MT is getting all the attention, as there will be a yellow service for Spring Half Term at the end of February.